When the Losers Write History

How the Confederacy Lost the Civil War but Won the Narrative

Part 2: Power & Memory

In the first installment of this series, we examined how authority determines what is preserved, emphasized, and obscured in the historical record. This essay turns to a more unsettling question: What happens when those who lose a definitive war retain the institutional capacity to define its meaning? The history of Confederate commemoration demonstrates that military defeat does not automatically translate into narrative displacement. It reveals how institutions, political coalitions, and public memory can survive the outcomes of the battlefield.

Whoever said that history is written by the victors never considered the aftermath of the American Civil War. Beginning with the attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861 and ending with the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Court House in April 1865, the Civil War was the deadliest conflict in American history. Between 620,000 and 750,000 soldiers died in the conflict—more American fatalities than in all other U.S. wars of the nineteenth century combined. Of those dead, approximately 360,000 were Union soldiers and roughly 260,000 were Confederates. The demographic consequences for the South were catastrophic: historians estimate that nearly one in four military-age white men in the Confederacy perished. Entire towns lost a generation. Infrastructure lay in ruins. The Confederate government ceased to exist.

The losses fell heavily on the Confederacy. By every measurable standard imaginable — military, political, and economic — the Confederacy was defeated by the better-equipped Union forces.

The phrase that insists that the victors write history persists because it appears to describe a rule of power. Armies that prevail secure territory and authority. Governments that survive shape textbooks, monuments, and civic celebrations. The narrative of victory becomes a permanent fixture in the public memory of Americans.

Yet its definitive defeat did not extinguish its ideology. Following the Civil War, the South complicates the belief about who gets to record what occurred in the pages of history books.

In 1865, the Confederate States of America collapsed. Its political experiment ended. Its armies surrendered. It failed in its explicit objective: the preservation and expansion of slavery. Once again, by any conventional measure, the South were indeed the losers.

Despite their obvious defeat, they erected monuments to celebrate Confederate traitors decades later.

Slavery and Secession

The cause of the war is not obscure in the documentary record. Secession declarations and speeches from Confederate leadership explicitly identified slavery as central to their political project.

Roger Hartley’s analysis of secession-era materials demonstrates that Southern states left the Union to preserve the institution of slavery. Commissioners sent throughout the South to encourage secession warned that Republican political victory threatened slaveholding security.

Alexander Stephens, the Confederacy’s vice president, declared publicly that the new government’s “cornerstone” rested upon the proposition that “the negro is not equal to the White man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition.”

The Confederacy did not frame itself as ambiguous. It announced its racial foundations openly.

Defeat Without Political Extinction

The precarious political order that had sustained the secession of Southern states was not permanently dismantled.

Reconstruction imposed federal oversight and temporarily restricted former Confederate officials from seeking public office, but there were no sweeping prosecutions for treason and no enduring political disqualification. Within a generation after the war, white Southern Democrats — who described themselves as “Redeemers” — had reclaimed control of state governments and congressional delegations.

The Confederacy lost the war, but it did not suffer the lasting consequences of political extinction. In this instance, the South did indeed rise again.

It was newly freed Black Americans who had to suffer the consequences of the Confederacy’s defeat and the white rage that followed.

As federal protection receded, Black voters were systematically disfranchised through poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses. Segregation was codified into law, and racial violence became an instrument of political control.

Black political participation collapsed. Paramilitary groups such as the White League and Red Shirts suppressed organizing through intimidation and murder. Southern states rewrote their constitutions to institutionalize the disfranchisement of Black people. Sharecropping systems entrenched economic dependency. Convict leasing reproduced coerced labor. Lynchings enforced a racial hierarchy through terror.

Southern whites found a way to regain their authority. Southern Blacks bore the cost of white supremacy.

Federal Intervention During Reconstruction

The Union victory preserved the United States and resulted in the ratification of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. Congress enacted the Enforcement Acts to suppress racial terror and protect Black voting rights. For a brief period, Black political participation expanded dramatically across the South.

Yet federal protection weakened as Northern commitment to Reconstruction declined.

The Equal Justice Initiative documents how racial violence intensified during the 1870s as white paramilitary groups attacked Black voters and Republican officials. Terror campaigns were coordinated and often tolerated by local authorities.

At the same time, judicial interpretations narrowed the reach of the Reconstruction amendments, weakening federal enforcement authority.

By the turn of the twentieth century, white Southern political leaders had regained control.

Disfranchisement as Policy

Michael Perman’s study of Southern disfranchisement demonstrates how, between the 1890s and the early 1900s, every former Confederate state rewrote its constitution to eliminate most Black voters from the electorate.

Poll taxes, literacy tests, property requirements, and complex registration systems were designed not merely to regulate elections but to restructure political power.

These reforms were defended publicly as necessary to restore “order” and “good government.” In practice, they created what Perman describes as a legalized system of political inequality.

Black citizens were excluded not accidentally but systematically.

The Confederacy had been defeated on the battlefield. White supremacy was reconstructed in law.

Lynching and Racial Terror

Law alone did not sustain the new order. Brutal violence was the mechanism that reinforced it.

The Equal Justice Initiative’s comprehensive study of lynching documents thousands of racial terror lynchings between 1877 and 1950. These killings were often public spectacles designed to intimidate entire communities.

Victims were frequently accused of minor social infractions, perceived breaches of racial etiquette, or fabricated crimes.

One early twentieth-century observer described lynching as a method used “not merely to wreak vengeance, but to terrorize and restrain” Black Americans.

Law and terror operated together in a symbiotic relationship. Disfranchisement removed the political power of Southern Blacks. Violence suppressed dissent.

Constructing the Lost Cause

The reinterpretation of the defeat of the Confederacy was an organized and deliberate effort. By no means was it organic.

The story of the Lost Cause emerged in the aftermath of the Civil War in the late nineteenth century. The defeat of the Confederacy was reframed as an honorable attempt to protect Southern society and its way of life rather than a failed rebellion to preserve slavery. For Southerners, the era of Reconstruction was viewed as corrupt, white supremacy was deemed necessary to maintain a semblance of order, and memories about the Old South were influenced by narratives of the Lost Cause. The goal of the Lost Cause was to minimize the role of slavery as the central reason for the Civil War and emphasize Southern valor, states’ rights, and constitutional virtues as the primary reasons why a war between the Northern and Southern states erupted. Most of these views were advanced by Confederate leaders, writers, and organizations such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

As Yale University history professor and Pulitzer Prize winner David Blight argues, national reconciliation privileged reunion over emancipation. In the South, this shift became institutional through Lost Cause narratives.

Adam Domby demonstrates how postwar advocates fabricated records, altered pension rolls, and manipulated public memory to minimize slavery’s role in secession. Confederate defeat was reframed as honorable resistance rather than failed rebellion. Roger Hartley’s analysis of Confederate monument advocacy reveals systematic denial of slavery’s centrality despite overwhelming documentary evidence.

The Lost Cause narrative did not emerge organically from grief. It was constructed through deliberate distortion.

Defeat became moral vindication. Rebellion became heritage.

Monuments and the Militarization of Memory

The physical landscape of the South changed accordingly.

The major wave of Confederate monument construction coincided with the entrenchment of segregation and disfranchisement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These monuments did not rise in the immediate aftermath of the surrender. They appeared decades later, during the consolidation of Jim Crow.

Thomas J. Brown’s study of Civil War memorial culture demonstrates how monument construction contributed to the militarization of public memory and to the normalization of sectional valor narratives.

Public monuments functioned as civic declarations. They shaped how communities interpreted the past and defined legitimate authority in the present.

They were not archival markers. They were instruments of political memory.

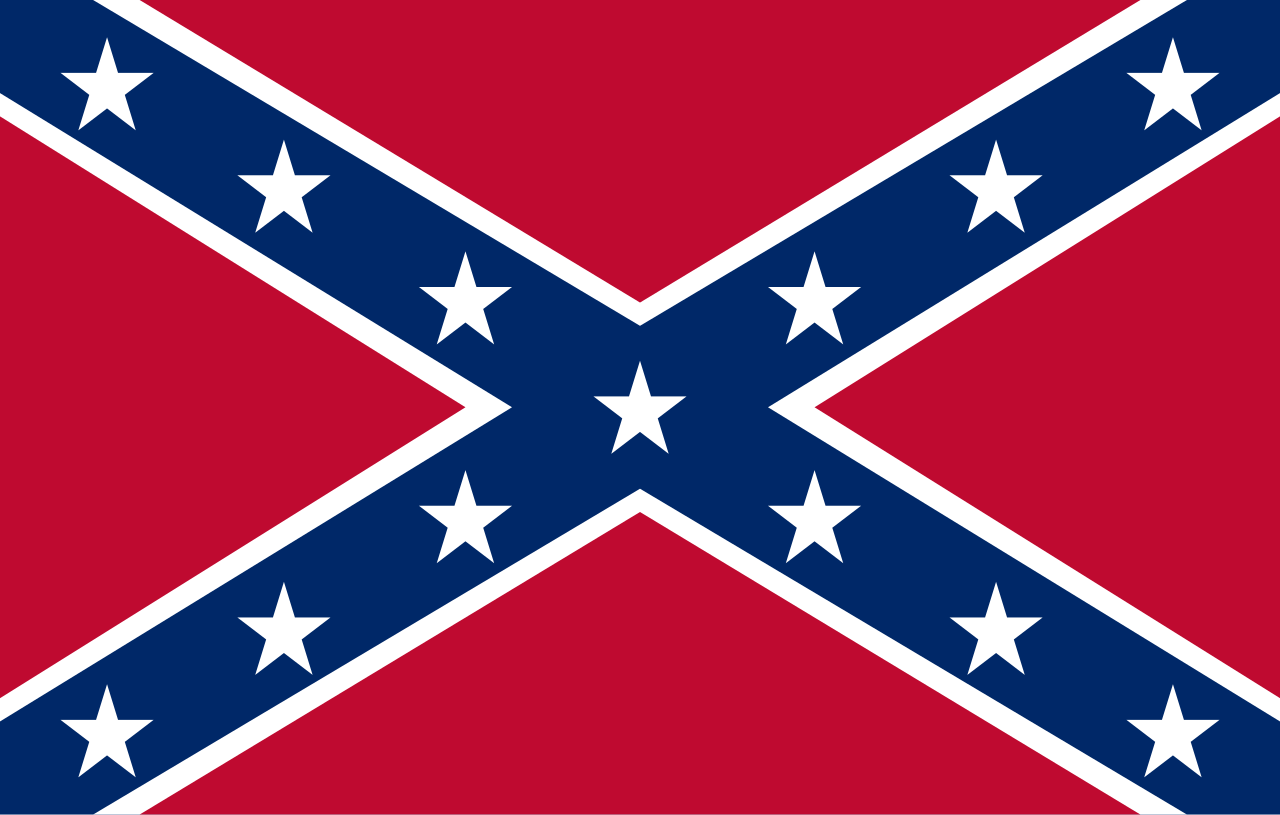

Confederate Symbols and Racial Attitudes

Confederate imagery did not remain confined to statues.

The Georgia state flag controversy illustrates the relationship between Confederate symbolism and contemporary racial politics. Scholarly analysis of public opinion and identity surrounding the flag demonstrates that attachment to Confederate imagery correlates strongly with racial attitudes and conceptions of Southern identity.

Symbolism carried political meaning.

The resurgence of Confederate imagery during moments of racial tension was not incidental. It reflected continuity between historical memory and contemporary power.

Stone and Sovereignty

Most Confederate monuments were erected between the 1890s and 1920s—during the consolidation of Jim Crow. Their placement on courthouse lawns and campuses signaled authority.

At the 1913 unveiling of “Silent Sam,” Confederate and Civil War veteran Julian Shakespeare Carr declared:

“The present generation scarcely takes note of what the Confederate soldier meant to the welfare of the Anglo-Saxon race… When the ‘bottom rail was on top’… they saved civilization… I made my boast then that if a negro wench was found on the streets of Chapel Hill, I would horse-whip her…”

Reconstruction was cast as racial inversion. Violence against Black people was presented as civic virtue. The monument did not mourn the defeat of the South. It celebrated restored white supremacy.

Symbols in Motion: The Flag, the Klan, and Waves of Monuments

Stone monuments fixed memory in place. The Confederate battle flag carried it into motion.

The second Ku Klux Klan, founded in 1915 at Stone Mountain, wrapped itself in Confederate imagery. By the 1920s, it claimed millions of members.

Monuments normalized a racial hierarchy; the Klan sought ways to enforce it through threats, violence, and intimidation.

Confederate symbolism surged again during resistance to the Civil Rights era. After Brown v. Board of Education (1954), Southern states invoked Confederate imagery in defiance of the landmark Supreme Court ruling. Between the mid-1950s and late 1960s, a second yet smaller wave of monument installations occurred. In 1956, Georgia redesigned its state flag to include the Confederate battle emblem amid resistance to desegregation pressures at the federal level.

The pattern is consistent: Confederate symbols intensified when federal authority threatened the racial hierarchy of the South.

Political Party Power Before Realignment

After Reconstruction, the Democratic Party dominated the South as it had in the antebellum era. The “Solid South” defended segregation and local control.

The Republican Party, once associated with emancipation, became marginal in Southern state politics after 1877. Nationally, it increasingly emphasized economic growth and limited federal intervention in regional racial governance.

This equilibrium held until federal civil rights legislation destabilized it.

The Return of Federal Authority: 1964–1965

Federal intervention returned in the 1960s.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited the denial of voting rights in federal elections on technical or discriminatory grounds and regulated literacy tests. It limited the discretionary barriers that had sustained disfranchisement.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 expanded federal oversight of state voting procedures, targeting jurisdictions with histories of discrimination.

These statutes directly confronted the disfranchisement systems established at the turn of the twentieth century.

For the first time since Reconstruction, the federal government reasserted authority over Southern electoral practices.

Continuity and Realignment

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 renewed federal protections for Black Americans and federal enforcement for integration initiatives. Southern Democrats resisted federal intervention. Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona, running against Lyndon Johnson in the 1964 presidential election, managed to carry several states in the Deep South in 1964.

Political allegiances shifted during this tumultuous period. Scholars describe this as a realignment. The coalition defending racial hierarchy—once fixtures in the Democratic Party—migrated across the aisle to join the Republican Party.

The monuments did not move. The electorate did. In this instance, they made ideological moves.

Confederate Memory in the 21st Century

Confederate symbolism did not disappear in the madness of Y2K as the twentieth century ended. Hundreds of monuments and public markers remain standing. In some cases, Confederate statues were relocated and reinstalled on private land. Lawmakers in Southern states have passed legislation in recent years to protect monuments, ensuring that Confederate memory remains anchored in public spaces.

The politics of memory continues.

What the Losers Won

The Confederate States of America failed at every possible level. They failed militarily, politically, economically, and even constitutionally.

Yet the guardians of the Confederate narrative were able to establish more positive interpretations of their legacy in the Southern states and blur the lines between victory and defeat in the rest of the country by changing the course of historical narrative.

American history textbooks adopted a more neutral and sympathetic tone about the motives behind Southern secession. The issues of states’ rights and federal overreach receive far more attention than the brutality of slavery. Public spaces have been filled with Confederate traitors instead of American heroes. Confederate symbolism is often connected to state identity. The most insidious of all is that Southern secession has been reframed as a celebration of Southern heritage.

Victories on the battlefield could never guarantee the dominance of any narrative, let alone the Southern view. In the end, political coalitions evolve, institutions endure, and memory remains contested.

Now we are left with a final rhetorical question: Should the United States honor those who took up arms in defense of slavery? Public monuments are not neutral archives; they are declarations of what society honors. A nation may study insurrections or document rebellions. To memorialize a rebellion in bronze is to endorse it in principle.

The debate over Confederate monuments is not about erasing history. It is about defining the moral boundaries of public honor.

To Be Continued…

The next installment takes us back to the present. If Confederate symbols surged during moments of racial retrenchment, contemporary battles over monuments, curricula, and public space reveal that the struggle over memory has not ended. The question is no longer who lost the war, but who currently controls its meaning.